Hyde's Shorthand

Hyde's early notebooks, from 1774 to November 1777, are lost or missing. It is possible that Impey appropriated them for his use when writing up the printed cases which were then sent to England. In the existing notebooks, he used a form of shorthand when he wrote comments about other court members that he did not want them to read. A selection of these passages is below.

Early modern shorthand systems are very useful because the basics can be easily varied to achieve a secure cipher while still writing in phonetic English. Between 1602, when the first shorthand manual was printed, and 1950 there were probably 400 different shorthand systems. Many lawyers learned shorthand to keep casebooks small enough to carry. Hyde used James Weston’s shorthand. He could be reasonably assured that no one could read it but himself. Hyde was not reserved – he wrote in forceful longhand, recording all opinions in cases including his own – but by 1780, that was no longer wise; dissension had split the court and the future was uncertain.

After the brief truce on the Supreme Council, when Hastings and Francis worked together to petition Parliament regarding the Kashijora case, Hastings insulted Francis during a Council meeting. Francis challenged him to a duel which took place in August 1780. Hastings won and wounded Francis, who returned to England. Hastings again had a majority on the Supreme Council and pushed through a proposal to appoint Impey the judge of a newly-formed Sadr Diwani Adalat. Impey was now the Chief Justice of two rival court systems, one appointed by Parliament and the King, the other owned and operated by the East India Company. Impey was now the Chief Justice of two rival court systems with overlapping jurisdictions.

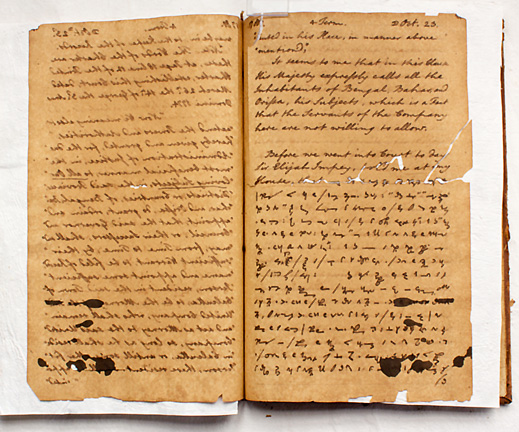

Figure 1 - Justice John Hyde’s first significant shorthand entry, Oct. 23, 1780, when learning of Sir Elijah Impey’s appointment to be Superintendent of the Sadr Diwani Adalat (central civil court).

Hyde wrote his first significant shorthand passage when he learned of Impey’s new position (see Fig. 1). He began in longhand “Before we went into Court today Sir Elijah Impey, told me at my House, that” and then transitioned to shorthand:

since he saw me last Thursday he had received notice of his appointment to be judge of the Sadr Diwani Adalat: he said further “and I have accepted it.” Impey said also “I think I might prevent that interference with the court which might happen if it was in other hands: I shall send all cases to the court that properly belong to it”: I said “I understand it was only a court of appeal”: Impey answered “no I understand it is also a court of general jurisdiction in causes [cases] above a set sum”: I said nothing to Impey implying approval nor disapproval but turned the discourse to the news that Sir Eyre Coote in the Duke of Kingston had got over the sands called the Braces:

In return for cooperating with the Supreme Council in limiting the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, Impey received an additional salary of Rs. 5,000 per month, plus Rs. 600 per month for expenses, or about three-fourths his Supreme Court salary of £8,000. He was put in a position to distribute patronage as well, appointing friends and relatives to salaried positions attached to the new court system. This appointment took place before the Bengal Judicature or Amending Act of 1781. It removed a burden from Hastings’ shoulders and placed a knowledgeable judge in charge of a larger system of justice, but it also ignored the directives of the Regulating Act, which forbade the Council or Court from taking any gifts or income other than their salaries. It also created a conflict of interest for Impey as head of the two court systems. Hyde was shocked and angry. His ink spill on the passage in Fig. 1 is rare in his handwriting. Hyde knew that Impey would now bend to Hastings’ will. Hyde knew his opinion was now in the minority and he must conceal his opinions if he wanted them to survive. He continued:

I do greatly disapprove of it because I think it must nearly render Impey dependent on the Governor General and Council and consequently partial to their wishes in . . . almost every cause of value that is brought into the court; and because the very appearance of it bends his opinion in many important questions; the extent of jurisdiction to be granted to him may well compromise the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Bengal: and how is it to be expected that he should decide against that authority: I think it a vast degradation of him to accept of such office in the service of the Governor General and Council or of the Company and on the appointment and to be held at the will and pleasure of the Governor General and Council [this is] a direct breech of the Act 13 G. 3rd which prohibits his taking presents or any other emolument than the salary . . . the only excuse I know for his accepting an employment is inconsistent with the duty of his office and so degrading is that he has six children to provide for and is never able to save much out his salary of 8000 pounds a year; but this I think a very mean and poor excuse.

Secure in the privacy of his shorthand, Hyde began recording Impey’s changing judicial opinions. The judges had agreed on many issues for their first six years, maintaining a façade of unanimity, but after Impey accepted the Superintendency of the Sadr Diwani Adalat, unanimity was over. This was especially obvious in the issue of jurisdiction over zamindars. When the Court first heard Aagya Takki v. Rani Bhabani in July 1780, Hyde and Impey had both been of opinion that Bhabani, the female zamindar of Rajshahi, was subject to the Court’s jurisdiction. When the case resurfaced in 1782, Hyde noted that although his and Chambers’ opinions had remained the same, Impey’s had changed. Impey no longer believed Bhabani was subject to the Court’s jurisdiction. Hyde began in longhand “Now” then switched to shorthand:

Impey said he inclined to know it proved her not subject to the jurisdiction; then I am sure Impey and I were of opinion it proved she was subject to the jurisdiction . . . Chambers inclined to think she was not subject: Chambers has been uniform and consistent: Impey has changed and varied particularly of late:

It had taken just over a year, but Hastings had won by bribery what he could not win by other means. Hyde alone still upheld the Supreme Court’s wide view of jurisdiction, but now outnumbered, his position was moot. Cases the Supreme Court once would have heard were now being heard by Impey’s Sadr Diwani Adalat. Impey’s power was growing at the Supreme Court’s expense, as Hyde recorded in his notebooks:

I attribute to Impey’s desire introduce the jurisdiction of the court; and to his desire to draw as much jurisdiction he can to the Diwani Adalats of which he is the head as much jurisdiction as he can: which some people attribute to his desire to raise money from the cases brought before him; for many people here accuse him though I hope falsely with being corrupt: and of late Impey talks in a very different style from what he used to do.

Impey had adjusted to the customs of the ruling culture in Company-run Calcutta. He had become part of the Company rather than being a check on it, abandoning his original judicial principles and his mandate from Parliament and the King.

Impey had also virtually abandoned the Supreme Court since his new superintendency required time and travel. By December 1780, Impey was at Murshidabad for the session and Hyde began the standard notebook roll call as “Present. Hyde. alone.” As sole judge on the bench, he had no peer for consultation or conversation. The observations and thoughts he recorded in shorthand were those that, in the past, he could have said to Lemaistre or another colleague.

Impey was not the only judge to feel the draw of clientelistic power relations. Like Impey, Chambers had maintained political ambitions to be appointed to the Supreme Council for the higher salary and greater power. He also had a growing family and saw the only route to financial success lay through Hastings. Hyde recorded in shorthand that after Impey received his appointment, Chambers sought a similar arrangement with Hastings. Chambers received his award when the Company Army conquered the Dutch settlement of Chinsurah in July 1781, nine months after Impey became Superintendent of the Sadr Diwani Adalat. Hyde wrote in shorthand:

the minute for Sir Robert Chambers to be Superintendent of the Court of Justice to be established at Chinsurah is done today; Sir Robert told me of it on Monday July 9th which was the first time I heard of it: . . . Chambers said he found he had no chance of being in the Council; that no position would be appointed but those whom Hastings chose: that he could save very little out his salary . . .

By now, Hyde had become more wary about protecting his narrative. He backdated this entry to July 7, several days before he learned of the appointment. Chambers’ additional salary was Rs. 3,000 a month with Rs. 2,426 per month for staff, two-thirds his Supreme Court salary of £6,000 per year. Hyde was upset that another brother-on-the-bench had compromised his integrity. Chambers too would be beholden to Hastings’ will. Hyde ended this shorthand entry “I will take nothing from the Governor and Council nor from the Company.” Hyde’s refusal to act illegally in Bengal in 1781 was so radical it had to be hidden from the public eye.

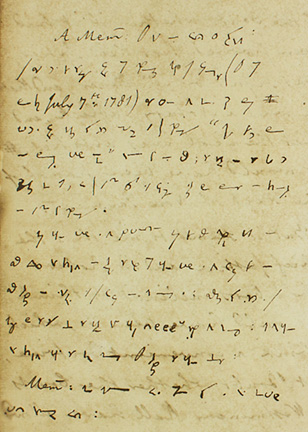

Figure 2 –Shorthand entry from March 8, 1782, recording a conversation with Lady Chambers while “going along in coach.”

From this point forward, whenever Hyde observed corruption among his colleagues, he recorded it in shorthand in his notebooks, hiding the entries within ongoing court cases. His observations are refreshing, often capturing fragments of conversations as they occurred. He began one shorthand entry with “A Memo” in abbreviated English and then switched into shorthand “which has no connection to this cause [case]” (see Fig. 2). This entry recorded a brief exchange with Chambers’ wife. Hyde had been traveling in a palanquin when he met Lady Chambers traveling in a coach with a friend, Mr. Hosea. Hyde joined them in the coach and Lady Chambers brought up the topic of her husband’s appointment. In shorthand Hyde wrote “Lady Chambers used these words alluding to his appointment ‘we have tried honor and honesty long enough’ meaning that now they, her husband and herself, had departed from it, by his taking profit into consideration instead of honor and honesty . . .” Hyde then noted that William Hosea, Lady Chambers’ friend, made her stop before she went any further. Despite Chambers’ absenteeism and corruption, Hyde was fond of him and Chambers appeared more and more frequently in his shorthand and later in court as well. It is crucial that these passages were in shorthand because Chambers inherited Hyde’s notebooks and Lady Chambers inherited them in turn.

For the Court’s first six years, Impey and Hyde had acted mostly in unison to set precedents. Hyde had argued for the strongest judiciary. Impey had been more moderate, and Chambers generally held that the judiciary should be subservient to the executive. After Impey was appointed to the Sadr Diwani Adalat, he changed his opinions to align with Hastings’, limiting the power of the Supreme Court and transferring it to the Company’s Adalats. As Hyde had feared, Impey bent himself to Hastings’ will. Chambers, who kept such a low profile on the court and also fell prey to desire for money and power, later resurrected himself and became a competent participaing Chief Justice. And Hyde gave up his ambitious program for creating an ideal court (although he continued to record his more controversial thoughts in shorthand).

Histories | Prior Legal Structures in Bengal | The Regulating Act of 1773 | Contentious Cases on the Supreme Court | . . . | Resolutions

Note: Historical summaries were written by Carol Siri Johnson and Andrew Otis.