COPAN BENCHMARK

This site has been chosen as a benchmark because Copán (Ko - pahn) represents the remains of a once great indigenous civilization in the Americas (Mesoamerica). The Mayan ruins provided evidence of pre-European complex civilizations in the Americas. The ancient Maya were noted mathematicians and astronomers whose pyramids aligned with the constellations. The architecture at Copán reflects this and also contains one of the most accomplished examples of Mayan architecture, the Hieroglyphic Stairway, which contains the single longest written Mayan inscription.

Lost for centuries the architectural remnants of ancient Mayan civilization were rediscovered in the jungles of Central America during the nineteenth century. During a diplomatic mission John Stephens and Frederick Catherwood discovered Copán in 1839 on an exploration of the Honduran jungles. Realizing the magnitude of their discovery Stephens and Catherwood spent many months exploring the ruins of Copán documenting and drawing the architectural and artifact remains. Today Copán is listed among the United Nations UNESCO World Heritage sites

Copán is located in Honduras on the west bank of the Rio Copán in the Copán Valley. The area was a fertile riverbed that had a reliable source of fresh water and farmers moved into the Copán Valley circa 1000BC. It was during the Classic Maya period (250 - 900) that the area began to flourish and the great Mayan cities, including Copán were built. Its citadel and imposing public squares characterize its three main stages of development.

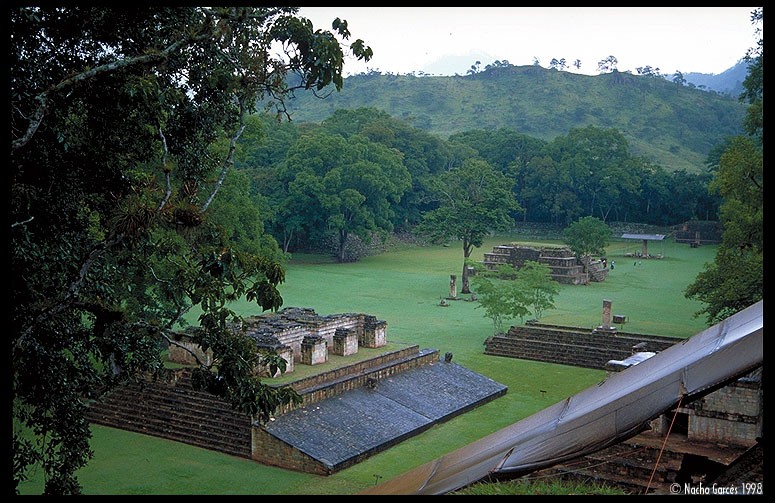

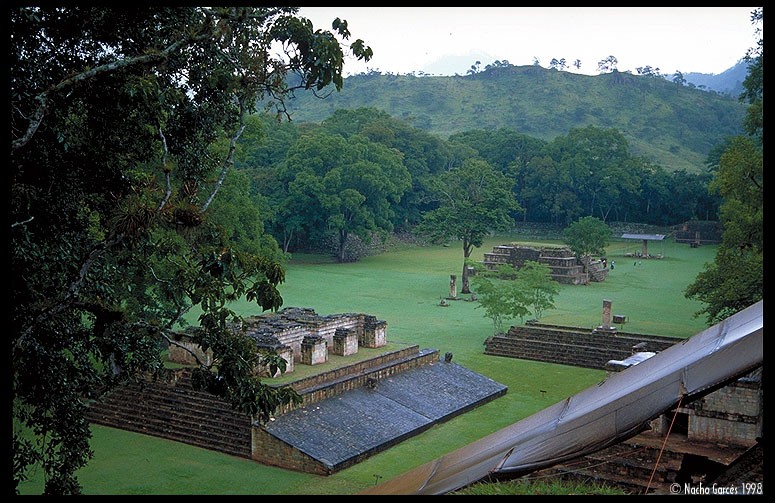

The City of Copán consists of a huge group of structures atop an artificial mound with five adjoining plazas and several outlying districts. The acropolis, the main building group that comprises this benchmark, covers a twelve-acre area and is 125 feet at its highest point. The focal point is the pyramid, a ritual structure that is a series of terraces rising to a flat summit (like a Sumerian ziggaurat). Immediately west of the pyramid smaller pyramids, temples and platforms surround a rectangular courtyard. To the east lies another plaza enclosed by terraces, a temple and buildings heavily ornamented with sculptured friezes. The temple doorway is in the form of a serpent's mouth.

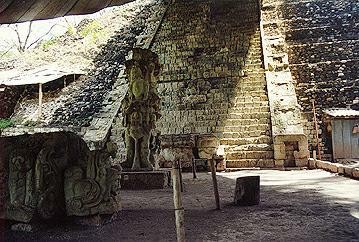

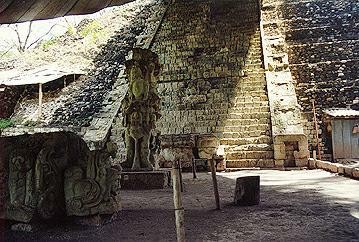

One of the most striking architectural features of the acropolis is the Temple of the Hieroglyphic Stairway, which is considered by many to be the most spectacular achievement of Copán's builders. The temple is a terraced pyramid that is ascended by a flight of stairs thirty feet wide and sixty-five feet high. The sixty steps of the stairway are flanked by decorative ramps and every stone riser is carved with hieroglyphics. The stairway contains approximately 2500 individual glyphs and is the longest single Maya inscription.

Other architectural features of the acropolis include a ball court constructed of an "I" shaped stone floor bordered on two sides by slanting walls attached to platforms crowned with temples. North of the ball court the City opens to the Great Plaza. The Great Plaza is a courtyard with a number of stelae and altars carved in high relief with human figures, mythical creatures, religious symbols and hieroglyphs. These stelae and altars were erected to commemorate historic events and the passing of specific time intervals.

The ruins of Copán were originally discovered in 1570 by Diego Garcia de Palacio, but were lost again to the jungle until the British Stephens and Catherwood expedition of 1839. The ruins of Copán have been studied since their rediscovery, though most early researchers did not believe that the indigenous people could have created such an advanced society. Early scholars formulated a romanticized utopian view of the ancient Maya. Credit for the ruins was given to the Lost Tribes of Israel, the Egyptians and the Phoenicians to name a few. However twentieth century studies, which have been conducted by a wide range of scholars have humanized the ancient Maya proving many of Stephens' original hypotheses concerning the complex nature of Mayan civilization to be accurate. He correctly surmised that the ruins were the remains of an indigenous New World group and that the human portraits on the monuments deified kings and heroes and that the writing systems recorded the history of these people.

The ancient Maya were one of many complex cultures and civilizations that thrived in the area known as Mesoamerica. The culture area of Mesoamerica is defined by a series of distinct cultural adaptations that were shared among the people inhabiting the area of central and southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and the western half of Honduras. The shared adaptations included architectural styles and features (including the pyramidal platforms supporting masonry structures, the playing of a rubber ballgame, a shared pantheon of deities as well as a shared calendrical system.

The Mayan civilization is divided into three periods, the pre-Classic (2000BC - AD250), the Classic (subdivided into the Early Classic 250-600 and the Late Classic 600-900) and the post-Classic (900 to the collapse or the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in 1519). During the Classic period populations in the Mayan region began to focus around ritual centers, which led to a degree of urbanization. In the Copán area all the power was gathered into the hands of one family circa 435AD. This gathering resulted in a dynasty that would rule throughout the Classic period. Copán became one of the most important and influential Mayan sites.

At the time of its rediscovery the City of Copán was nothing more that a spectacular pile of ruins. Time and exposure to the elements including occasional earthquakes led to the collapse of almost all the buildings there. Limestone structures, faced with lime stucco, were the hallmark of ancient Maya architecture. The Maya developed several unique building innovations, including the corbeled arch which was a false arch achieved by stepping each successive block, from opposite sides, closer to the center, and capped at the peak. However, while other Mayan cities used good quality lime mortar for their constructions, the residents of Copán were limited to using lime for plastering floors and the exterior surfaces of masonry buildings due to a relative paucity of limestone in the Copán Valley. Instead a mud mortar was used for the buildings rubble fills. Once the city was abandoned the plaster caps on top of the structures began to crack enabling water and tree roots to penetrate the structures.

Despite the site's ruinous state, Stephens and Catherwood recognized the magnitude of their discovery. Stephens published his account accompanied by Catherwood's drawings (Incidents of Travel in Central America) in 1841 and recognized that once word of the ruins reached the public there would be many visitors seeking to remove objects to museums in the west. To prevent this, Stephens purchased the lease on the land and Harvard University's Peabody Museum was granted permission to conduct the first investigations of Copán.

The information that has been learned about Mayan culture and society is invaluable. As part of the investigations conservation has occurred on many of the features of the Copán and other Mayan sites. This has demonstrated how the Mesoamerican pyramids at one time dominated the landscape. Until the construction of the Flatiron building in New York City in 1903, the Mesoamerican pyramids were the tallest structures in the Americas.

This site can be used to address the following themes of World History as recommended by the New York State Regents.

This site can be used to address the following themes of World History as recommended by the New York State Regents.

1. Pre-industrial Societies - There were many factors common to all pre-industrial societies regardless of their geographic location. Copán and its residents faced and dealt with these like many others. Many of the issues are familiar to modem city dwellers such as crowded and unsanitary conditions. Like many other pre-industrial societies there was also a proliferation of communicable diseases in Copán.

2. Features of a Civilization - Civilizations are defined by certain characteristics, all of which are exhibited at Copán. Among the features of a civilization are organized government; complex religion; job specialization; social classes; arts and architecture; (large scale) public works and a writing system.

3. Hierarchies - There was a distinct class system in ancient Maya times. The nucleation of society around a central place, Copán, led to the exploitation of the lower ranks of society by the elite or ruling class. Each city had its own ruling chief who was surrounded by nobles who served as the military leaders and officials for public works to collect taxes and enforce laws. Also, between the ruling class and the farmer/laborer, there was an educated aristocracy who were scribes, artists and architects. Priests were another rank in society as only they could perform the elaborate religious ceremonies that ensured a good harvest and success in war. However, most of Mayan society was comprised of farmers who paid their taxes in food and helped to build the temples.

4. Ritual Sacrifice - the ancient Maya practiced ritual sacrifice, both animal and human. The pyramids, which were a focal point of Mayan cities, were constructed as temples and served ritual purposes. Among the most common animals sacrificed were jaguars and animal sacrifices were often buried in tombs located within the pyramids with other ritual objects. Human sacrifices became more frequent toward the collapse of the Mayan civilization and often during periods of drought and famine. The human sacrifice ritual began one year prior to the sacrifice when the honored victim was taken from his or her family to live a life of luxury. In some instances, after the human sacrifice, the body of the victim was thrown to the crowd and consumed. It has been proposed that this was a means for the population to get protein in their diet.

5. Writing Systems - The Ancient Mayan codex was indecipherable for many decades. In the past 25 years since the code was broken there have been ongoing translations of Mayan writings. While the Ancient Egyptians kept detailed records of their economy, the Mayan writings focus on the history of their rulers, the elite, their society and their view of the world. Most Mayan sites had multi-roomed structures that probably served as royal palaces as well as centers for government affairs. Historically significant events, such as accessions and the capture or sacrifice of royal victims, were recorded on stone stelae and tablets. A large portion of the writings are concerned with the Mayan calendar system and astronomical studies.

6. Indigenous Populations - The ancient Maya were indigenous to Mesoamerica and even though their society collapsed centuries before the arrival of western explorers, Mayan groups remained. The Maya can be used as an example of the treatment of indigenous populations following western exploration. Mayan society still survives today and millions of people in Mexico and Guatemala still speak Mayan dialects.

7. Technology - With great population increases in their cities the Maya sought to meet the demands of the populace. One technological innovation, also seen in ancient Rome, was the development of an aqueduct system to provide the houses and apartments with running water.

8. Collapse of Civilizations - history notes many great civilizations that have fallen (the Roman Empire for example). Ancient Maya civilization, their centralized government and cities collapsed circa 1000. There have been many investigations and theories as to why it fell, but the most promising one focuses on an extended drought coupled with increased populations leading to widespread famine and disease. The centralized governments could no longer support the large-scale nucleation of the population and the groups abandoned the cities dispersing into the countryside. While not as dramatic as being overthrown by an invading group, the reasons for the collapse of the great Mayan cities pose many questions as to the nature of human groups and their needs. The Maya did not disappear they dispersed and they were still present, in much smaller groups, upon the arrival of Europeans.

9. Exploration and Contact with Indigenous Populations - The Maya culture suffered a fate similar to many indigenous groups upon the arrival of Europeans. This topic is a direct lead- in to colonialism and the impacts and implications of colonialism in a global arena.

10. Agriculture - The ancient Maya were an agricultural society. Agriculture has been the basis of human civilization and there are many forms of agriculture and it is the agricultural revolution in a region that leads to the development of civilization. The Maya cleared the rain forests and practiced what is known as "slash and bum" farming. Slash and bum farming requires that a field be left fallow for 5 to 15 years after only 2 to 5 years of cultivation. However, there is also evidence that fixed raised fields and terraced hillsides that caught and held rainwater were used in some areas. In these areas the Maya also built channels to drain the excess rainwater.

12. Trade - A great deal of Mayan cities' wealth had to do with a widespread trade network. The Mayan region had an extensive road system. The roads were made of packed earth. Common trade items were honey, cocoa, cotton cloth and feathers.

In English this site can be used to explore non-western myths and folklore. The ancient Maya, like many indigenous groups of the Americas, have a rich tradition of folklore. This tradition provides great insight into the culture and its views about the world around them. As evidenced with the Maya, many cultures rationalize or incorporate drastic changes to their society into their mythology. The Maya rationalized the arrival of Cortez and the Spanish as the arrival of their plumed god Quetzalcoatl. Literary themes that can be addressed are the qualities exhibited by major characters in world literature. Many cultures have some form of story-telling tradition, be it oral or written, with many of the stories containing common themes and characters. The heroic figures and themes in Homer's the Iliad and the Odyssey can be seen in different forms in pre-Colombian myths and stories.

In English this site can be used to explore non-western myths and folklore. The ancient Maya, like many indigenous groups of the Americas, have a rich tradition of folklore. This tradition provides great insight into the culture and its views about the world around them. As evidenced with the Maya, many cultures rationalize or incorporate drastic changes to their society into their mythology. The Maya rationalized the arrival of Cortez and the Spanish as the arrival of their plumed god Quetzalcoatl. Literary themes that can be addressed are the qualities exhibited by major characters in world literature. Many cultures have some form of story-telling tradition, be it oral or written, with many of the stories containing common themes and characters. The heroic figures and themes in Homer's the Iliad and the Odyssey can be seen in different forms in pre-Colombian myths and stories.

Connections between this site and science are through diet and health. The ancient Maya were farmers who had a small range of staple crops that included maize, beans, Chili peppers and gourds (squash). The Maya used these staples in many combinations that fulfilled their nutritive needs. Also, the Maya built their cities in lush fertile areas, which were quickly reclaimed by the jungles of Central America. The area of the Copán Valley has a wide range of ecological and bio-diversity. Many areas surrounding Mayan ruins are now used as the location of ecological field schools forming natural outdoor laboratories or are the site of ecological parks. Another aspect that can be explored is communicable disease in cities and the effects of hygiene. Copán, like many pre-modern cities, had a number of residents in close quarters and communicable diseases were an ongoing problem. The lack of sanitation/garbage disposal and clean running water are just two factors that caused the problem to fester.

Connections between this site and science are through diet and health. The ancient Maya were farmers who had a small range of staple crops that included maize, beans, Chili peppers and gourds (squash). The Maya used these staples in many combinations that fulfilled their nutritive needs. Also, the Maya built their cities in lush fertile areas, which were quickly reclaimed by the jungles of Central America. The area of the Copán Valley has a wide range of ecological and bio-diversity. Many areas surrounding Mayan ruins are now used as the location of ecological field schools forming natural outdoor laboratories or are the site of ecological parks. Another aspect that can be explored is communicable disease in cities and the effects of hygiene. Copán, like many pre-modern cities, had a number of residents in close quarters and communicable diseases were an ongoing problem. The lack of sanitation/garbage disposal and clean running water are just two factors that caused the problem to fester.

Connections between this site and mathematics are the exploration of ancient numerical systems. The Maya developed a complex numbering system of their own and were noted mathematicians. Instead of ten digits, the Maya used a base number of 20 referred to as a base 20 Vigesimal numbering system. (20 as a grouping number was used by many cultures throughout world history. This was because people have twenty digits (fingers and toes). Each number (which may be a succession of dots or lines) represents a place value. The numbers are arranged vertically with the highest place value at the top. Because the base of the number system was 20, larger numbers were written down in powers of 20. We do that in our decimal system too: for example 32 is 3xl0+2. In the Maya system, this would be lx20+12. Numbers were written from bottom to top and adding was just a matter of adding up dots and bars Maya merchants often used cocoa beans laid out on the ground to do their calculations. The Maya are also one of the few ancient societies to have an understanding of the concept of zero. Also, scaled images could be used to calculate the angles of the pyramids of Mesoamerica. Mayan pyramids, like many monumental structures built by ancient cultures, were designed to align with the constellations.

Connections between this site and mathematics are the exploration of ancient numerical systems. The Maya developed a complex numbering system of their own and were noted mathematicians. Instead of ten digits, the Maya used a base number of 20 referred to as a base 20 Vigesimal numbering system. (20 as a grouping number was used by many cultures throughout world history. This was because people have twenty digits (fingers and toes). Each number (which may be a succession of dots or lines) represents a place value. The numbers are arranged vertically with the highest place value at the top. Because the base of the number system was 20, larger numbers were written down in powers of 20. We do that in our decimal system too: for example 32 is 3xl0+2. In the Maya system, this would be lx20+12. Numbers were written from bottom to top and adding was just a matter of adding up dots and bars Maya merchants often used cocoa beans laid out on the ground to do their calculations. The Maya are also one of the few ancient societies to have an understanding of the concept of zero. Also, scaled images could be used to calculate the angles of the pyramids of Mesoamerica. Mayan pyramids, like many monumental structures built by ancient cultures, were designed to align with the constellations.

Some recommended activities to use with the site are to explore the plight of indigenous civilizations around the world and consider activism issues to support or dispute the positions of the indigenous groups. Explore the many different indigenous games and how they have survived to the present day. Explore the Mesoamerican ballgame - one of the first team sports in human history.

Some local buildings which relate to themes addressed in this unit and could be used for additional study are:

Heye Collection - Located at the Museum of the American Indian the Heye Collection is the personal collection of George Gustav Heye. It represents one of the largest collection of Native American materials containing over one million items from indigenous peoples throughout the western hemisphere. The collection is a valuable material record of many indigenous cultures and peoples of the Americas.

Some recommended activities to use on a visit to this local site are to consider how the plight of the Native American has been represented in the museum. Have students consider the history and treatment of the Native American in the Americas and how the museum has chosen to represent the many different and diverse Native groups once found in the Americas.

Other buildings/sites that relate to this benchmark and could be used for additional study are:

Tikal - the Largest Mayan city, its ruins are located in Guatemala. Teotihuacan - A monumental Aztec site located in the Valley of Mexico (100-750). The Aztec were for a time contemporaneous with the Maya though they occupied a smaller region focused in northern Mexico. Often thought of as more warlike the Aztec were an imperial state governed by one ruler.

Tenochtitlan - an Aztec site located in Mexico City Machu Picchu - an Inca site located in Peru. The Inca were another of the four great pre- Columbian Mesoamerican societies. Located in South America the Inca civilization reigned from approximately 1200-1535. Their reign came to a brutal end with the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadors who decimated in the Inca army of approx 40,000. Inca society was strictly hierarchal with one ruler, the Inca.

Some other ideas, which could be explored or expanded on having to do with this site, are astronomy (the Maya were achieved astronomers whose observations of the cosmos were highly detailed and accurate); the preservation of Copán; its current use as a tourist destination and the ways that visitors may hurt or change an historic site.

MODULES

Back to Top

Global History I

Civilizations of the Americas

World Literature

Native American myths, legends, and folktales

Algebra - Math A

Rational Functions

Inverse Variation

Biology

Chemical Regulation

The Human Nervous System

Plant Maintenance and Plant Nutrition

RECOMMENDED READINGS

Back to Top

Baudez, Claude-François. Maya Scultpture of Copán: The Iconography. University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

Baudez' text is an in-depth look at the construction and detail of Mayan Sculpture at Copán. The text does not limit itself to desciptive text but looks at the sculpture and iconography of the stelae and various structures, including the Hieroglyphic Stairway, at Copán as an extension of Mayan culture and society. The iconography on Mayan stelae and other structures has been an important element in the study of the ancient Maya. These architectural storybooks are a guide to the history of this complex ancient society. Baudez' descriptive text is accompanied by an historical overview placing the analysis and interpretations of the iconography in context.

Fash, William L. Scribes, Warriors and Kings: The City of Copán and the Ancient Maya. Thames and Hudson, New York 1991.

William Fash is one of the leading scholars of Mayan studies. This text is a comprehensive look at what scholars have learned about the Maya culture and history through the exploration of their architectural and archaeological remains. Fash discusses all aspects of Mayan life from Copán's spectacular architecture to the ritual aspects of the society. Theories are also presented about why the Mayan culture collapsed and an account of how this civilization was rediscovered. Fash's account also documents the many different disciplines, including architecture, archaeology, linguistics and art history, that have come together to explore and document the Ancient Maya.

Gallenkamp, Charles. Maya: The Riddle and Rediscovery of a Lost Civilization. Viking, New York, 1985.

Gallenkamp's text is a popular account of the Maya that provides the reader with an introduction to the rediscovery of the ruins and the basic information that has been learned about this great civilization. The selected chapters highlight the rediscovery of the ancient Maya, through the rediscovery of the Mayan ruins by Stephens and Catherwood. Gallenkamp provides an admirable account of the Stephens and Catherwood expedition and its importance to the rediscovery of the ancient Maya.

Sexton, James D. editor. Mayan Folktales: Folklore from Lake Atitlán, Guatemala. Anchor Books, New York 1992.

The selected text is the Mayan Creation Myth. The myths translated and edited by James Sexton are part of the oral tradition of the Maya. Collected in the twentieth century they have undergone changes from their original form to include the Spanish influence on the Maya.

Sharer, Robert J. et.al.. Continuities and Contrasts in Early Classic Architecture of Central Copán in Mesoamerican Architecture as Cultural Symbol. Jeff Karl Kowalski editor. Oxford University Press, New York 1999.

This article discusses the nature and evolution of Classic Mayan architecture as evidenced in ongoing and recent archaeological research at Copán. The authors particularly focus on the "question of continuity of form and function in successions of superimposed buildings". The area of the acropolis at Copán has demonstrated many layers of continual use and construction. They consider the cultural significance of the site as continual development led to three independent focal points of construction to eventually converge into a single monumental elevated complex. The article, through its own research, demonstrates how human populations attach meaning to space and continue to reuse places sometimes attaching new cultural meanings or functions to those spaces.

Weaver, Muriel Proter. The Aztecs, Maya, and Their Predecessors: Archaeology of Mesoamerica. Academic Press, New York 1993.

This is a standard textbook on Mesoamerica. The selected readings focus on the City of Copán, the Mayan region and ancient Mayan culture as explored through their calendar system and writings. The selected text is well suited for students.

Early classic Architecture

Baudez, Claude-François. Maya Scultpture of Copán: The Iconography. University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

Baudez' text is an in-depth look at the construction and detail of Mayan Sculpture at Copán. The text does not limit itself to desciptive text but looks at the sculpture and iconography of the stelae and various structures, including the Hieroglyphic Stairway, at Copán as an extension of Mayan culture and society. The iconography on Mayan stelae and other structures has been an important element in the study of the ancient Maya. These architectural storybooks are a guide to the history of this complex ancient society. Baudez' descriptive text is accompanied by an historical overview placing the analysis and interpretations of the iconography in context.

Fash, William L. Scribes, Warriors and Kings: The City of Copán and the Ancient Maya. Thames and Hudson, New York 1991.

William Fash is one of the leading scholars of Mayan studies. This text is a comprehensive look at what scholars have learned about the Maya culture and history through the exploration of their architectural and archaeological remains. Fash discusses all aspects of Mayan life from Copán's spectacular architecture to the ritual aspects of the society. Theories are also presented about why the Mayan culture collapsed and an account of how this civilization was rediscovered. Fash's account also documents the many different disciplines, including architecture, archaeology, linguistics and art history, that have come together to explore and document the Ancient Maya.

Gallenkamp, Charles. Maya: The Riddle and Rediscovery of a Lost Civilization. Viking, New York, 1985.

Gallenkamp's text is a popular account of the Maya that provides the reader with an introduction to the rediscovery of the ruins and the basic information that has been learned about this great civilization. The selected chapters highlight the rediscovery of the ancient Maya, through the rediscovery of the Mayan ruins by Stephens and Catherwood. Gallenkamp provides an admirable account of the Stephens and Catherwood expedition and its importance to the rediscovery of the ancient Maya.

Sexton, James D. editor. Mayan Folktales: Folklore from Lake Atitlán, Guatemala. Anchor Books, New York 1992.

The selected text is the Mayan Creation Myth. The myths translated and edited by James Sexton are part of the oral tradition of the Maya. Collected in the twentieth century they have undergone changes from their original form to include the Spanish influence on the Maya.

Sharer, Robert J. et.al.. Continuities and Contrasts in Early Classic Architecture of Central Copán in Mesoamerican Architecture as Cultural Symbol. Jeff Karl Kowalski editor. Oxford University Press, New York 1999.

This article discusses the nature and evolution of Classic Mayan architecture as evidenced in ongoing and recent archaeological research at Copán. The authors particularly focus on the "question of continuity of form and function in successions of superimposed buildings". The area of the acropolis at Copán has demonstrated many layers of continual use and construction. They consider the cultural significance of the site as continual development led to three independent focal points of construction to eventually converge into a single monumental elevated complex. The article, through its own research, demonstrates how human populations attach meaning to space and continue to reuse places sometimes attaching new cultural meanings or functions to those spaces.

Weaver, Muriel Proter. The Aztecs, Maya, and Their Predecessors: Archaeology of Mesoamerica. Academic Press, New York 1993.

This is a standard textbook on Mesoamerica. The selected readings focus on the City of Copán, the Mayan region and ancient Mayan culture as explored through their calendar system and writings. The selected text is well suited for students.

Early classic Architecture

RECOMMENDED WEB SITES

Back to Top

Archaeology of the Ancient Mayan civilization of Mesoamerica

http://www.jaguar-sun.com/maya.html

This site has general information on many aspects of Maya culture both past and present. The site contains a listing of the Mayan pantheon; each deity is accompanied by an image of the hieroglyph that represents that god. There is also a resources page that lists other websites and books.

Copan Maya Net

http://www.mayanet.hn/copan/Index.htm

This is a comprehensive web site that includes photos, maps and a virtual reality tour of Copan. There is also information on the Mayan civilization and culture. This site is available in English and Spanish.

Copan Ruins

http://www.honduras.net/copan/

This tourism site provides general information about the ruins accompanied by images of the site including the museum and visitors center.

Copan Village Archaeology Museum

http://www.maya-archaeology.org/html/copanm.html

Multimedia museum site with artifacts and architecture movies and images of Copan. Many of the images are panoramic and are an adequate classroom substitute for a visit to Copan.

National Museum of the American Indian

http://www.nmai.si.edu/

Official website for the museum that houses the Heye collection. Though the museum focuses on North American Native groups the collection contains objects from many indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere. The site also has teacher information and public education resources focused on Native Americans in the United States.

Maya Astronomy Page

http://www.michielb.nl/maya/astro_content.html?t2=1014214289250

The Ancient Maya were adept astronomers who had a sophisticated calendar. This page briefly explains their astronomical and mathematical systems, as well as the Mayan calendar and writing system. There is a calendar converter that allows the translation of the Gregorian calendar to Mayan dates.

Maya Civilization Past Present

http://www.kstrom.net/isk/maya/maya.html

Comprehensive site with information and links about various aspects of Mayan life and culture. Some topics covered are traditional stories, language (including a pronunciation guide) and the mathematical system.

Saving the Maya Past for the Future

http://www.peabody.harvard.edu/profiles/fash.html

Website with general information about the Copan Sculpture Museum set up to preserve the remnants of Mayan history.

The Mesoamerican Ballgame

http://www.ballgame.org.

Site dedicated to the Mesoamerican ballgame. Includes information about the game, the museum tour and an interactive site to watch the game.

Back to Top

Back to Benchmarks

Back to the Main Page