I.

More esoteric research perseveres, and there’s a direct link between what I said at Interrupt2 with tonight’s presentation. Three years ago, my IRQ interruption introduced the newly born UnderAcademy College, brainchild of Talan Memmott, and what I’ll discuss now—Shy nag, a “code opera” recently staged in Newark—results from a collaboration that emerged from an UnderAcademy course titled TOO MANY COOKS, circa (circuits, circus) Fall 2012.

During Shy nag’s stage prep, co-director Louis Wells asked me to create an animation to use as a preface to the performance, indicating the fact that manipulating code is at its roots. Here it is:

II.

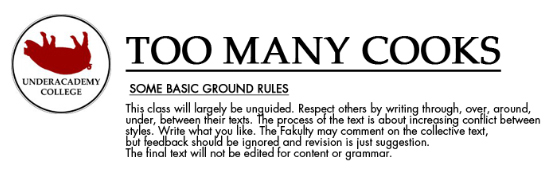

TOO MANY COOKS was a rare occurrence in which the number of faculty leading a pedagogical initiative outnumbered the students enrolled by a ratio of more than 2:1. The entire course revolved around a single Google Doc, which participants were encouraged to populate and freely edit at any time. Instructions were explained within Memmott’s course logo:

This class will largely be unguided. Respect others by writing through, over, around, under, between their texts. The process of the text is about increasing conflict between styles. Write what you like. The Fakulty may comment on the collective text, but feedback should be ignored and revision is just suggestion.

An e-book encapsulating the occasion has been produced, and is now available for free download via the UnderAcademy College WordPress site:

An interesting diversion occurred shortly after the course began. Progressing through, I was drawn toward the work of co-digressor Sonny Rae Tempest. I knew him a bit, and after reading his Daily Moment Art blog post “A Picture Worth 11,739 Words” (October 2, 2012), I became attentive to our common creative interests, particularly using spell-check as a compositional tool. Back-channeling, Tempest and I came up with a subplot to the course, called “So Many Pans”, and began posting some of our experiments. Just as we began jamming together, I was contacted by Kent MacCarter of Cordite Poetry Review, who asked me to submit work for their Interlocutor issue. So I proposed to Tempest that we put together something involving the “translation” of an image into readable text. We did, and Cordite published our “Exit Ducky”, which textualizes the issue’s cover image, along with a descriptive statement of process titled, “Picture Becomes Text, Becomes Writing: Software as Interlocutor”.

III.

The similar process Tempest and I used to make Shy nag’s libretto started by opening the image file of the TOO MANY COOKS logo as a Chinese character-encoded text file [see shynag-source.pdf, for best effect, press ctrl-shift-H once the file is open in Acrobat]. The resultant text became English via Google Translate [see translation1.pdf], and was subsequently processed and filtered through Word spell-check. Since the code is lengthy, over fifty pages, the output was large. A perpetually prismatic text, comprised of choices made among thousands of possible options the software provided, results. After the libretto was composed, Tempest translated the text into sound by utilizing the P22 Music Text Composition Generator. The resultant MIDI file was opened with Acid Pro 3 DAW (Digital Audio Workshop) software. He created three identical audio tracks (double bass, acoustic guitar, piano), manually transposing all notes into the appropriate range (per instrument) and into the key of D major. This process results in a score that is more than five hours long, the first seventy minutes of which was excerpted for the performance. A second audio track, compressing the whole soundfile produced by the code to seventy minutes, is layered into the performance mix. To make the projected imagery, the original hexidecimal code was broken into 24-bit sections to act as the hex code for HTML web colors. An HTML file was then created to consecutively fade from one color to the next, based on that partitioned hex, using JavaScript. Each color block is displayed in text above its color field [see https://web.njit.edu/~funkhous/2015/Shy-nag/colorfield/colortext.html].

IV.

In Spring 2013, I mentioned the libretto to colleagues in NJIT’s Theatre Department. They enthusiastically supported the idea of producing a performance—explaining their informal motto is, “we’re not afraid to fail”. During a series of Fall 2014 pre-production meetings it was decided a quickly choreographed staged reading, co-directed by Wells and Brian O’Mahoney, would occur in February 2015. A cast featuring students and alumni who they felt could contend with, and bring energy to the material was selected. A group reading happened in December (after which two potential actors declined to participate), and intensive rehearsals took place over two weeks in January.

A number of delightful things occurred. Reading between the lines, the co-directors painstakingly worked to identify a plot trajectory, or narrative arc, and determined or invented conceptual relationships existing between characters. They decided the overall setting would be similar to an academic conference panel.

Here’s some documentation, beginning with this clip near the beginning of the show—indicative of the action in general and introduces most of its conditional components:

Ludicrous stage directions were considered, sometimes influencing their choreography. Major characteristics of the script that had to be dealt with included a series of absurd “Ads”, as well as Choruses, that speckle the libretto.

Here’s a compilation of one style of Chorus:

Scene settings changed quickly, jumping between: “Sauna”, “End of a Bow”, “At tan balance”, “The lift: surface ban transient. Sound, queue. Coarse low?? Mats suit to sum. Hoxie pa”, “Almost marsh? Metaphorical panic testifies. Wet? Bared incorporated the wig. Sorrowful eve at basin’s fickle human chaos in Quantum Posts”, “Zoo of heteromorphy”, and “Jailing mountain peak”. Isn’t it all the same code?

Particularly relevant in the last segment there is the line, “I am the transient miscellaneous”, and it should be noted that my nine year old daughter Aleatory, after hearing the line “I circle screwed trampling” exclaimed, “In other words, they had sex!”—which proves to me the axiom that even in nonsense poetic logic may be detected.

Lighting and sound personnel, including a stage manager who attended every rehearsal and took copious notes (Alex Yoe), perfectly negotiated the material and co-directors’ instructions, providing an excellent setting for the performance. In the end, most aspects were kept simple: costumes were to be “business casual”, “scenes” were announced, with gesture, by one of the actors—who also indicatively used a flashlight as a spotlight when “Ads” were read. Two actors clacking clavés with one another signified a Chorus’ completion. Beyond what I’ve mentioned, there were few props: a lemon, a briefcase, trash can, small bag of feathers, water bottles and other sundries on the “panel’s” table; at the last minute, a copy of my Free Dogma title, pressAgain, was propped up.

Communication for the production was organized by Wells, using a Google Doc to organize production information, such as character mapping, rehearsal scheduling, and some “Notes to Actors”, including:

- Find your characters. Look over the text and find a tone, mood, emotion that the text seems to indicate. Don't look for story, look for tones.

- Look for POV about anything and everything in the text. Make it up, but choose one.

- Honor the punctuation. That is your map through the material. Let Chris talk punctuation.

- I need a Chicken, Jesus, and Satan Doll.

V.

Afterwards, two reviews appeared in the student papers. NJIT’s The Vector declared “There was no excuse for this…. It made me angry. I was angry that my time was wasted”, among many other negative impressions. Rutgers-Newark’s The Observer was more balanced in its reporting, objectively describing the event and including a mix of commentary from the audience: from “Shy nag was the worst production I ever had the misfortune of watching, it was illogical, incoherent, and unresolved”, to “very fascinating example of human impulse to have to make sense of chaos” and, “it was a refreshing piece, unlike that of the norm we are so used to”.

Addressing these points, I will note extreme satisfaction with the entire experience; the performance was successful on many registers, perhaps most of all because Wells, O’Mahoney, and the actors conspired to create something that just about anyone could watch and be stimulated by at least once. It should be noted that others who read these reviews opined that they were tremendously positive precisely because they reflect how the show exposed its audience to the idea of breaking code, making it into uncomfortable translation and expression.

VI.

With its point of departure I see this work as very much of the age, and not at all “for the ages” or joining a pantheon in a way some sort of classical work would. As an artist, Hakim Bey’s sense of potential for temporary autonomous zones—creating provisional spaces that elude formal structures of control, where information becomes a key tool that sneaks into the cracks of formal procedures—has always held appeal, and often effects structural modalities I become involved with. This particular show, wayward and off-the-wall, sponsored and supported by the institution, is a good example of a product that accomplishes this objective (as is, perhaps, the very occasion we have all gathered for).

At the time of its staging in Newark, I began seeing Shy nag as a wild new type of ekphrasis, writing from image. Shy nag signifies one of many new potentials for poetic composition, in which the subsurface encodings of information become alternatively rendered—a process involving destruction and construction both on automated/objective and subjective registers. When combined as, or within, an expressive sensorium, moments of visceral synthesis impress on an audience in surprising ways. Our stew of language, beyond practical sense, accumulates with humor, delivering the type of seated, psychic transportation such as is afforded by musical lyricism and sensory stimuli.

We have, by now, basically open sourced all of the material for further consideration via website. Similar processes could be applied to any of the Web’s millions of images. Thus, in terms of offering at least one direct interrupt to common contemporary dialogs about text and composition, let me pose this: we have all heard a lot of talk about big data; what about little data? In the lab, experiments with small, hidden data, existing beneath the surface, lost and in itself meaningless data that is veiled or rarely seen, devoid of evocative “feeling” on its own, may have as much value as its oft discussed “big” counterpart.

What else can be done with more limited amounts of common, ordinary, public information, even something that isn’t normally seen? Must we hang on to the concept that something will inevitably arise from nothing? Isn’t it possible to create nothing from something and perchance be enriched by it?