U.N. Report Sees New Pollution Threat

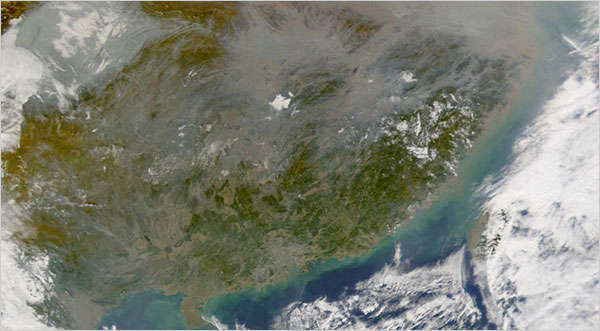

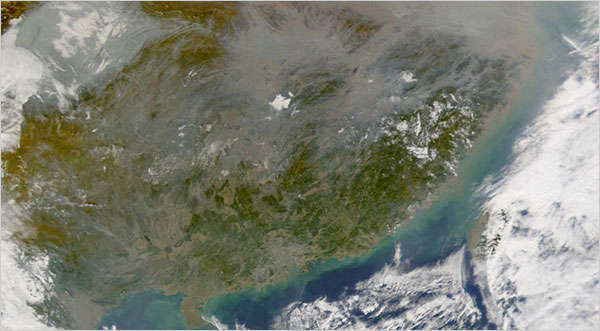

NASA/Goddard Space

Flight Center

A satellite image shows a dense blanket of polluted air over central eastern

China covering the coastline

around Shanghai.

The "Asian Brown Cloud" is a toxic mix of ash, acids and airborne particles

from car and factory emissions, as well as from low-tech polluters like wood-burning

stoves.

By

ANDREW

JACOBS

Published:

November 13, 2008

BEIJING — A noxious cocktail

of soot, smog and toxic chemicals is blotting out the sun, fouling the lungs of

millions of people and altering weather patterns in large parts of Asia, according to a report released Thursday by the United

Nations.

The byproduct

of automobiles, slash-and-burn agriculture, wood-burning kitchen stoves and coal-fired

power plants,

these plumes of carbon dust rise over southern Africa, the Amazon basin and North

America. But they are most pronounced in Asia, where so-called atmospheric

brown clouds are dramatically reducing sunlight in many Chinese cities and leading

to decreased crop yields in swaths of rural India, say a team of more than a dozen

scientists who have been studying the problem since 2002.

Combined

with mounting evidence that greenhouse gases are leading to a rise in global temperatures,

the report’s authors called on governments both rich and poor to address the problem

of carbon emissions.

“The

imperative to act has never been clearer,” said Achim

Steiner, executive director of the United Nations Environment Program, in Beijing, where the report, titled “Atmospheric Brown Clouds:

Regional Assessment Report With Focus on Asia,” was released.

The brownish

haze, sometimes more than a mile thick and clearly visible from airplanes, stretches

from the Arabian Peninsula to the Yellow Sea.

During the spring, it sweeps past North and South Korea and Japan. Sometimes the cloud drifts

as far east as California.

The report

identified 13 cities as brown-cloud hotspots, among them Bangkok, Cairo, New Delhi, Seoul and Tehran. In some Chinese

cities, the smog has reduced sunlight by as much as 20 percent since the 1970s,

it said.

Rain

can cleanse the skies, but some of the black grime that falls to earth ends up

on the surface of the Himalayan glaciers that are the source of water for billions

of people in China, India

and Pakistan. As a

result, the glaciers that feed into the Yangtze, Ganges, Indus

and Yellow rivers are absorbing more sunlight and melting

more rapidly, researchers say.

According

to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, these glaciers have

shrunk by 5 percent since the 1950s and, at the current rate of retreat, could

shrink by another 75 percent by 2050. “We used

to think of this brown cloud as a regional problem, but now we realize its impact

is much greater,” said Prof. Veerabhadran Ramanathan, who led the United Nations scientific panel. “When

we see the smog one day and not the next, it just means it’s blown somewhere else.”

Although

their overall impact is not entirely understood, Professor Ramanathan,

a professor of climate and ocean sciences at the University

of California, San

Diego, said the clouds might be affecting rainfall in parts of India and Southeast Asia, where monsoon rainfall

has been decreasing in recent decades, and central China, where devastating floods have

become more frequent.

He said

that some studies suggest that the plumes of soot that blot out the sun have led

to a 5 percent decline in the growth rate of rice harvests across Asia since the 1960s.

For those

who breathe the toxic mix, the impact can be deadly. Henning Rodhe, a professor of chemical meteorology at Stockholm University,

estimates that 340,000 people in China

and India

die each year from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases that can be traced

to the emissions from coal-burning factories, diesel trucks and kitchen stoves

fueled by twigs.

“The

impacts on health alone is a reason to reduce these brown clouds,” he said, adding

that in China, about 3.6 percent of the nation’s annual gross domestic product,

or $82 billion, is lost to the health effects of pollution.

The scientists

who worked on the report said the blanket of haze hovering over Asia and other parts of the world might be mitigating the

worst effects of greenhouse gases by absorbing solar heat or reflecting it away

from the earth. Greenhouse gases, by contrast, tend to trap the warmth of the

sun and lead to a rise in ocean temperatures.

Mr. Steiner,

the head of the United Nations environment program, said the findings complicated

the global-warming narrative. The brown clouds mask the impact of the greenhouse

gases, he said: Without the blocking effect of the smog, he said, climate change

would be far worse.

“All

of this points to an even greater and urgent need to take on emissions across

the planet,” he said.