To many African-Americans, the “socially conscious” lyrics of much of the “folk-rock” now fashionable among the “more adventurous bohemian white groups” came off as just “white kids playing around....The ‘protest’ is not new. Black people’s songs have carried the fire and struggle of their lives since they first opened their mouths in this part of the world....”With secular music, integration (meaning the harnessing of Black energy for dollars by white folks, in this case the music business) spilled the content open to a generalizing that took the bite of specific protest out (“You know you cain’t sell that to white folks).” [21]

Sure enough, the specific protest, palpable in Curtis Knight’s “How Would You Feel,” ensured it wasn’t a success in 1965. Even when Hendrix became an international superstar less than two years later, he had to cover Dylan’s song rather than the Curtis Knight song. The lyrics that Sly wrote for The Beau Brummel’s version of “Underdog,” with their repeated “I know how it feels,” lyrical hook, are similarly influenced by “Like A Rolling Stone,” but the blatant racial signifiers are ambiguous or even edited out. Had the song been released in late 1965, it’s doubtful most people would have realized it was written by a black man any more than other Dylan-influenced hits of that year (i.e. Los Hombres “Let It All Hang Out”); the anger is there, but also humor and a sense of fun; it can “pass” for white boys playing around.

The song combines other fashionable influences from the pop culture of 1965. Sociologists often claim the “underdog” is a particularly American myth, even in 2011 when the American Dream of “upward mobility” that seemed available during The Great Society (LBJ not the band) has been replaced by the most rigid class structure in the post-industrialized world. In 1964/65, the TV cartoon series, Underdog, was as popular as The Swim was, and many young people were gearing up for a new season (before he needed his super-energy pills).

The main 12-string guitar riff hook “out-Byrds the Byrds,” the heavy tambourine, hand claps and floor tom, are like Sly’s take on Motown’s funk brothers meets “Peggy Sue,” and Sal Valentino’s high-pitched but snarly lead vocals are delivered with a passion more like Them’s Van Morrison than the earlier Beau Brummel hits. The hurt and anger in the song is Sly’s, but when the young urban working class Italian American Sal Valentino begins by singing the fast internal rhymes, a “Dylan device” that should at least be traced back to Chuck Berry’s “Too Much Monkey Business,” the anger seems like it’s one he and Sly shared:

I know how it feels when you know you’re real

but every other time, you get a raw deal coz you’re the underdawg

I know how it feels when people stop, turn around and around

stare and signify a little bit-- don’t rate me [22]

Valentino could be referring to some “youth culture” badge of honor, or proto-freak flag like long hair, and Sly himself was “a very flashy black man, dressed in Beatles suits and this weird pompadour.” [23] But in The Beau Brummels’ version, the anger is about class as much as it is about youth culture. In 1964/65, the perspective of working class youth culture was making a comeback on top 40 radio [24] and “Underdog” is addressed to a big boss man who gives you a “raw deal” when you want a “fair shake” at least as much as it is to people making fun of your funny hat like Sonny Bono’s “Laugh At Me.”

In this sense Sal & Sly’s collaboration is analogous to the kind of integration Jazz had allowed in the 20s and 30s. As Le Roi Jones wrote in 1963: “The young white jazz musician (in contrast to the white liberal and sensual dilettante and the communist party during the Harlem Renaissance and Depression) at least had to face black American head-on...and they could not help but do this without some sense of rebellion or separateness from the rest of white America.” [25] Likewise, The Beau Brummels (in contrast to the white Pete Seeger folkies, Berkeley Nimbys, and the hippies of the Haight), at least seemed to understand that R&B “had created a music that offered such a profound reflection of America that it could attract white musicians...It made a common cultural ground where black and white America seemed only day and night in the same city and at their most disparate, proved only to result in different styles.” (38)

Structurally and thematically, the lyrics of “Underdog” are more like the early Dylan of “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna-Fall.” After the litany of social horrors in “Hard Rain,” the singer ends by standing on the water until he starts sinking. “Underdog” is also a song of working class perseverance and resolve; however comically portrayed (like the cartoon), it also means it. Super! Lines like “super free” cater to Valentino’s vocal and expressive strengths. “Sometimes I think I’m losin’ it but I can make it because I’m made of some kind of super special stuff!” and “First honesty, then destiny, then you can’t believe that I’ve done in my life just what I was supposed to.” I can hear Sly’s joy in verbal articulation he had kept mostly musical (or on the level of DJ patter) before; in the last verse especially, the palpable excitement in being able to honestly express his purpose, even though he’s “hiding behind” (shining through) Valentino’s voice.

In the second and third verses, the criticism is much more specific. Listen to Valentino sing, “too many people they get together go up one side and down they other, they try to make it sooo tough” against the backdrop of what was happening with Autumn Records and the San Francisco scene at the end of 1965, and its “I’m Not Your Stepping Stone” passion, garage-rock sound and proto-punk “Dylanesque” vocal phrasing, become a perfect description of their prodigal boss, Tom Donahue. Donahue was jumping ship, whether or not he could admit it to himself, let alone his employees including Sly & The Brummels.

Donahue had only come to the Bay Area a few years before Sly and The Brummels appeared on the scene, to escape a payola scandal in Pittsburgh. By the end of 1965, his lack of commitment to the established R&B/Mod scene in San Francisco, was revealing itself to the younger Bay Area raised Sly and Sal. Donahue stopped listening to Sly’s suggestions (for instance, to lure Billy Preston to the label) and kept deferring the live-album of Sly’s Cow Palace show. Instead, In late [November] ’65, with the Brummels’ hit records and incessant touring bringing money into Autumn, Donahue expanded [his] local roster, adding three new groups from the budding Haight-Ashbury scene.” [26]

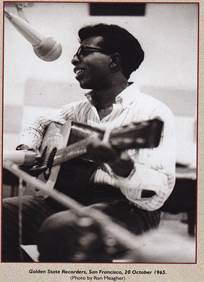

Sly dutifully tried to lend his talents and experience as producer, arranger and songwriter to create hit singles, but the new bands Donahue was bringing in, however popular live to a different (and apparently more LUCRATIVE) audience, were not studio-ready. It took over 45 takes to get a passable version of the Great Society’s first single, “Somebody To Love.” Sly’s exasperation is evident on the masters Alec Palao unearthed from the Autumn vaults. “As far as Sly was concerned, they were amateurs, and as far as they were concerned, he was Mr. Plastic-Hey-Baby-Soul.”(26)

As Donahue’s attention started drifting to the beatnik/folk-music/performance art/jazz and hippie scene and the upper middle class youths from the northern suburbs, resorts and the midwest migrating to the Haight, this reawakened the working class chip on both Sly and Sal’s’shoulder, as Donahue had gone up on their side and was now trying to come down the other. Yet, they’re (hilariously) defiant and stand their ground:

But understand...I know what to do.

You look down on me, and IIIIIIIII.....look down on you

I guess I’d rather be the underdog than to be in a fog sittin on a log

going down the river by the go nowhere...

no matter what you do to me, or try to make me be

I’m in contact with something sup-er free-ee...

Coz I understand....your mind is small...

no understanding...and that ain’t all...

In this working class mod anti-flake song, Sly has it both ways--bonding with Italian Sal against the fickle Irishman, and enjoying a little joke at the expense of the white protest song movement. Like The Thirteenth Floor Elevators or The Sonics, 15 years later it would be called punk (change it only slightly, thicken the guitar on the choruses, and it’s The Descendants or...). By the end, the song’s able to cathartically work out the hurt, the anger, the justified feeling of abandonment, with the realization that you can’t count on anyone, but you still got your sense of destiny and purpose; if anything, you’re more driven than ever to make it on your own, since now you’re left with no other choice. Well, almost. In the song’s last line, intended to be sung during the fade-out ending, Sal Sings: “leave it up to the human race, for destroying one of the human race, you ought to be ashamed of yourself.”

“Are You Sure? (Life Of Fortune And Fame),” the proposed flipside (or even A-side) for “Underdog,” is a beautifully haunting introspective, or even despondent, folk-rock piece, like Love’s “A Message To Pretty.” The two songs complement each other in the spirit of the best double-sided singles of that era. [27] Sung to an upper-class (presumably white) woman who the male singer fears is treating him like a “specimen,” “Are You Sure,” in Sly’s words:

was inspired by the real. Some party, some girl, back in Vallejo. The homecoming queen. Her parents were rich and she liked me alot. I didn’t understand it. It always happened like that, too. Yeah, I was her specimen. It’s important to whisper lyrics. Without knowing it, people hear the words better.” [28]

Both these songs were breakthroughs for Sly, and he returned to both of them with The Family Stone. Now very popular among retro-mods (many of whom don’t even know it’s a Sly Stone side), and record collector geeks in The Bay Area, “Underdog” remained unreleased; Donahue never even paid to get the tapes back from the studio, claiming financial difficulties, even as he was taking the money Sly and The Beau Brummels had brought into Autumn and pouring it into “The Great Society.”

Instead, for the next Beau Brummels single, Autumn chose the much less distinctive, but already in the can, cover of the Lovin Spoonful’s “Good Time Music,” blowing an opportunity to cash in on the folk-rock/garage rock craze, and show off Sly’s songwriting rather than New Yorker John Sebastian in helping the Beau Brummels transition (as bands like The Kinks were, single by single). “Good Time Music” bombed, a fitting swan song to Autumn Records, while other potential hits, like Billy Preston’s Sly-produced “Can’t You Tell” and “I Remember,” lie in hock. [29]

By the end of 1965, it was starting to seem that Donahue was doing everything he could, however indirectly, to subvert Sly. This didn’t really make sense, unless maybe they really didn’t want to be a successful nationally-known label in the first place. After all, they only released “C’mon And Swim” after L.A. based Warner Brothers rejected it. By April 1966, only four months later, Donahue sold the label, and The Beau Brummels, to Warner Brothers as a tax-write-off. Like the label that had signed the Viscaynes five years earlier, Autumn was never as important for Donahue than their live shows and management deals. No wonder Sly felt “demoted,” even though Sly could now buy his parents a house in a middle class black SF neighborhood and Donahue bought him a Cadillac and ostensibly “promoted” him. He might have been moving up just a little too fast!

Sly, through no fault of his own, found himself stuck in a historical moment when mass-culture was starting to become less local, less working class and more racially segregated than the local-based mass culture he entered only 5 years earlier. [30] A musical chameleon, Sly helped enliven the music-centric culture of San Francisco more than any of his contemporaries. He offered a multi-dimensional community through records and the radio, as well as through small clubs with topless entrepreneurs, but when Bill Graham muscled his way into the scene, it had the almost immediate effect of cutting out the very ground of the cultural coalition Sly was putting together to create a context in which he, and his music, could be more free. The culmination of years of struggle was slipping away...