Soft Dielectric Materials

ABSTRACT: Soft dielectrics are electrically-insulating elastomeric materials, which are capable of large deformation and electrical polarization, and are used as smart transducers for converting between mechanical and electrical energy. While much theoretical and computational modeling effort has gone into describing the ideal, time-independent behavior of these materials, viscoelasticity is a crucial component of the observed mechanical response and hence has a significant effect on electromechanical actuation. We have a constitutive theory and numerical modeling capability for dielectric viscoelastomers, able to describe electromechanical coupling, large-deformations, large-stretch chain-locking, and a time-dependent mechanical response. Our approach is calibrated to the widely-used soft dielectric VHB 4910, and the finite-element implementation of the model is used to study the role of viscoelasticity in instabilities in soft dielectrics.

Details:

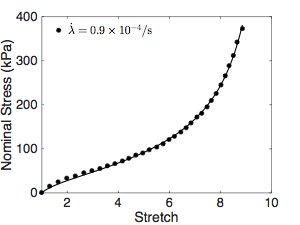

Simple Tension of VHB

Nominal stress as a function of stretch in simple tension for VHB. Here solid lines corresponds to our model fit, while the dotted curves correspond to experimental data.

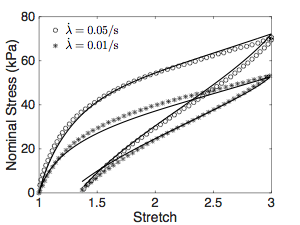

Electrocavitation

Contour plots of (a) the maximum logarithmic strain, and (b)the normalized electric potential. The three rows correspond to applied normalized electric potentials. We note that the strain contours corresponding to the maximum applied electric field (bottom left contour plot) indicate the extreme localization occurring after the onset of the electrocavitation instability.

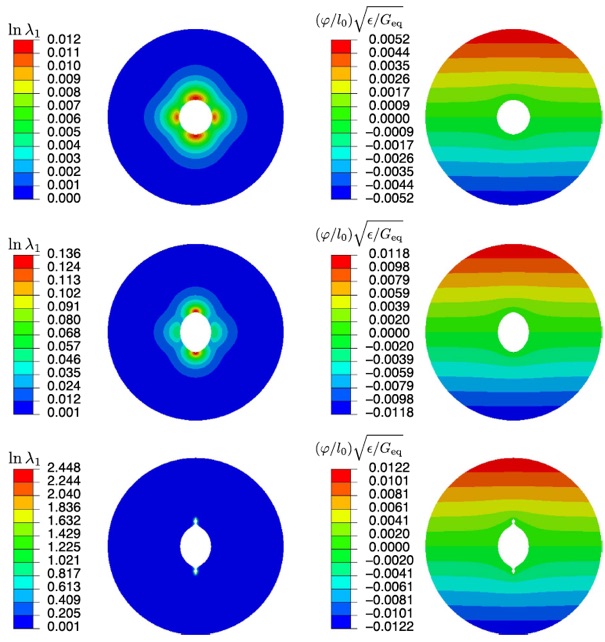

Non-Isothermal Validation

Non-isothermal inhomogeneous model validation. (a) Prescribed displacement and temperature profiles, and the resulting (b) force–displacement curves, and (c) force–time curves.

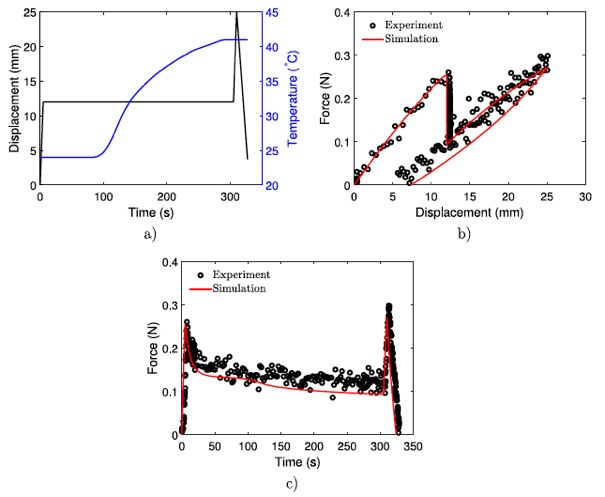

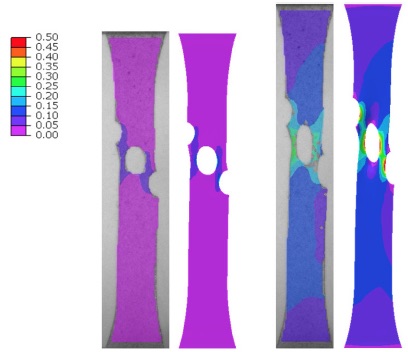

Comparison of Hencky strain component E22 for the non-isothermal inhomogeneous uniaxial deformation between the experimentally measured (left) and simulated (right) validation at prescribed displacements of (a) 3.7 mm, and (b) 12.4 mm.